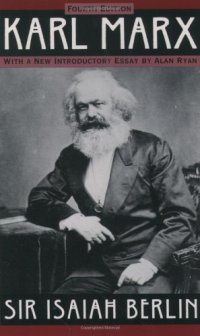

Ebook: Karl Marx: His Life and Environment, Fourth Edition

Author: Sir Isaiah Berlin Alan Ryan

- Genre: Other Social Sciences // Philosophy

- Year: 1996

- Publisher: Oxford University Press

- Edition: 4

- Language: English

- pdf

Marx's theory of history and society is a `wide and comprehensive doctrine which derives its structure and basic concepts from Hegel and the Young Hegelians, its dynamic principles from Saint-Simon, its belief in the primacy of matter from Feuerbach, and its view of the proletariat from the French communist tradition.'

Berlin remarked that Hegel's importance lies in the scholarship of social and historical studies. Pushing back the claim that only the scientific method can prove the science of society, Hegel asserted that such radical empiricism fails to account for the individual character in a specific moment in time of history. History undergoes `major transitions in the past marked by large-scale revolutionary leap.' Calling this process dialectical, he theorized that `each age inherits something new from its predecessors so change is plainly not repetitive.' This progressive movement is towards what Hegel called, the Spirit, the highest level of self-consciousness in relation to the universe.

The origins of Marx's eventual theory can be traced to other theorists. Feuerbach believed that `all ideologies whether religious or secular are often an attempt to provide ideal compensation for real miseries.' Marx deemed `all institutions, churches, economic systems, forms of government, moral codes and culture' as illusory, abstract distractions that promotes `collective self-deceptions' and encourages alienation, `the substitution of imaginary relations between, or worship of, inanimate objects or ideas for real relations between, or respect for, persons.'

From Saint-Simon, Marx adopted and elaborated the theory of class struggle. In formulating `his view of the evolution and correct analysis of industrial society,' Marx learned from Louis Blanc's organization of labor. Marx's analysis on the nature of the class struggle - the irreconcilability between the classes of exploiter and exploited, the `propertyless proletariat being the lowest rung of the social scale' - derives in part from Weitling's theory that `only the ruined and the outcasts can be relied on to carry through the revolution to its conclusion, since others will inevitably stop short when their own interests are threatened.'

Berlin's thesis emphasized Hegel's influence on Marx. In The German Ideology, Marx accepted and applied Hegel's framework and recognized that `the history of humanity is a single, non-repetitive process, which obeys discoverable laws.' While Hegel considered `the nation a stage in the development of world spirit,' Marx attributed `the system of economic relations that govern society.' Both Hegel and Marx treated history as a phenomenology and `the vision of history as a battlefield of incarnate ideas.' Hegel's concepts and structures are pervasive in Marx's doctrines.

Marx's inflexible position on revolution can be derived from his strict observance of determinism, letting him see the world in terms of black and white. An individual's class identification is preordained by the position on the socio-economic map - one will do what is necessary to protect and secure private interests respective to the material situation. Hence, he opposed the moralizing of Grun and Hess since `men's acts were in the end determined by their moral character'; the outcome of the French Revolution exposed a vacuity of moral goodness in men. After 1848, Marx retreated from the opportunism of a bourgeois-proletariat alignment in order to `preserve the purity of the party, and its freedom from any compromising entanglement.' Retracting from the Communist Manifesto after the Paris Commune, Marx later advocated `the destruction of the state root and branch, not merely to seize it,' and thereby picked up a new moniker - `the Red terrorist doctor.'

Without foreseeing a state redress, Marx's Das Kapital portends `the fusion of rival firms in a ceaseless process of ruthless competitions' and that `machinery does not indeed increase profits, relatively or absolutely, but eliminates inefficient competitors.' At the end of the amalgamation process, only the largest and most powerful groups are left tin existence.' He predicted that `Big Businesses will destroy laissez fair and individualism.' Berlin attributed `the application of Marxist cannons of interpretation for forming the scientific study of historically evolving economic relations, and of their bearing on other aspects of the lives of communities and individuals.'

Berlin's narrative also sketched the human side of Marx, his camaraderie with Engel, his hostilities and suspicions towards his contemporaries and his love for his wife and children. The most interesting is the delineation of his ideological development influenced by his ego and unrelenting character.

Berlin remarked that Hegel's importance lies in the scholarship of social and historical studies. Pushing back the claim that only the scientific method can prove the science of society, Hegel asserted that such radical empiricism fails to account for the individual character in a specific moment in time of history. History undergoes `major transitions in the past marked by large-scale revolutionary leap.' Calling this process dialectical, he theorized that `each age inherits something new from its predecessors so change is plainly not repetitive.' This progressive movement is towards what Hegel called, the Spirit, the highest level of self-consciousness in relation to the universe.

The origins of Marx's eventual theory can be traced to other theorists. Feuerbach believed that `all ideologies whether religious or secular are often an attempt to provide ideal compensation for real miseries.' Marx deemed `all institutions, churches, economic systems, forms of government, moral codes and culture' as illusory, abstract distractions that promotes `collective self-deceptions' and encourages alienation, `the substitution of imaginary relations between, or worship of, inanimate objects or ideas for real relations between, or respect for, persons.'

From Saint-Simon, Marx adopted and elaborated the theory of class struggle. In formulating `his view of the evolution and correct analysis of industrial society,' Marx learned from Louis Blanc's organization of labor. Marx's analysis on the nature of the class struggle - the irreconcilability between the classes of exploiter and exploited, the `propertyless proletariat being the lowest rung of the social scale' - derives in part from Weitling's theory that `only the ruined and the outcasts can be relied on to carry through the revolution to its conclusion, since others will inevitably stop short when their own interests are threatened.'

Berlin's thesis emphasized Hegel's influence on Marx. In The German Ideology, Marx accepted and applied Hegel's framework and recognized that `the history of humanity is a single, non-repetitive process, which obeys discoverable laws.' While Hegel considered `the nation a stage in the development of world spirit,' Marx attributed `the system of economic relations that govern society.' Both Hegel and Marx treated history as a phenomenology and `the vision of history as a battlefield of incarnate ideas.' Hegel's concepts and structures are pervasive in Marx's doctrines.

Marx's inflexible position on revolution can be derived from his strict observance of determinism, letting him see the world in terms of black and white. An individual's class identification is preordained by the position on the socio-economic map - one will do what is necessary to protect and secure private interests respective to the material situation. Hence, he opposed the moralizing of Grun and Hess since `men's acts were in the end determined by their moral character'; the outcome of the French Revolution exposed a vacuity of moral goodness in men. After 1848, Marx retreated from the opportunism of a bourgeois-proletariat alignment in order to `preserve the purity of the party, and its freedom from any compromising entanglement.' Retracting from the Communist Manifesto after the Paris Commune, Marx later advocated `the destruction of the state root and branch, not merely to seize it,' and thereby picked up a new moniker - `the Red terrorist doctor.'

Without foreseeing a state redress, Marx's Das Kapital portends `the fusion of rival firms in a ceaseless process of ruthless competitions' and that `machinery does not indeed increase profits, relatively or absolutely, but eliminates inefficient competitors.' At the end of the amalgamation process, only the largest and most powerful groups are left tin existence.' He predicted that `Big Businesses will destroy laissez fair and individualism.' Berlin attributed `the application of Marxist cannons of interpretation for forming the scientific study of historically evolving economic relations, and of their bearing on other aspects of the lives of communities and individuals.'

Berlin's narrative also sketched the human side of Marx, his camaraderie with Engel, his hostilities and suspicions towards his contemporaries and his love for his wife and children. The most interesting is the delineation of his ideological development influenced by his ego and unrelenting character.

Download the book Karl Marx: His Life and Environment, Fourth Edition for free or read online

Continue reading on any device:

Last viewed books

Related books

{related-news}

Comments (0)